Some months ago a friend introduced me to the French expression ‘metro – boulot – dodo’. The phrase captures a set of interconnected feelings: that an inordinate amount of time is lost commuting each morning (metro), that days themselves are the fiefdom of work (boulot), and that once you have returned home, you are so shattered it is impossible to conceive of anything else other than getting ready for bed (dodo). That such arrangements have prompted little in the way of collective unrest might seem surprising. Why do so many of us, with such fleeting lifespans, subject and submit ourselves to the grind? The need for money, for one. Depending on circumstances, there are employment related conditions to visas and access to health care, dependent family members to support. Yet there is also a sense that it cannot be fear alone which animates us to take heed of the alarm clock, but some form of passionate attachment to work too, what we imagine it makes possible. It is this excess or surplus that have led some to suggest that there is an affective dimension to the economy, that modes of production do not simply allocate and distribute resources but also organize desire.

Taking up this idea of an affective composition of the economy, Frederic Lordon argues that there have been three ‘regimes of desire’ in the history capitalism. The first coincides with Marx’s own time and is dominated by the ‘spur of hunger’. Workers are driven into factories by the sad affect of fear, the desire to avoid the ‘material evil’ of destitution that awaits those without work or any alternative means of subsistence. A second regime emerges around standardized mass production, Fordism, whereby the degradations and fragmentations of industrial labour are offset by increased access to consumer goods. This period is characterized by a ‘joyful alienation’, one in which work must be endured but is compensated by the extrinsic pleasures of consumption. Subjects disaffiliate from their status as workers and symbolically identify with capital, as consumers. Finally, in the post-Fordist or neoliberal regime, the stability of the company job is replaced by insecurity: factories close, capital takes flight, work is deskilled and automated. Precarity, however, is presented as opportunity. Fears of declassement are evened out with joys that are now felt to be intrinsic to work itself, which, freed from rigid hierarchies and stultifying bureaucratic norms, is where subjects discover their passion, achieve self-realization, and manifest their dreams.

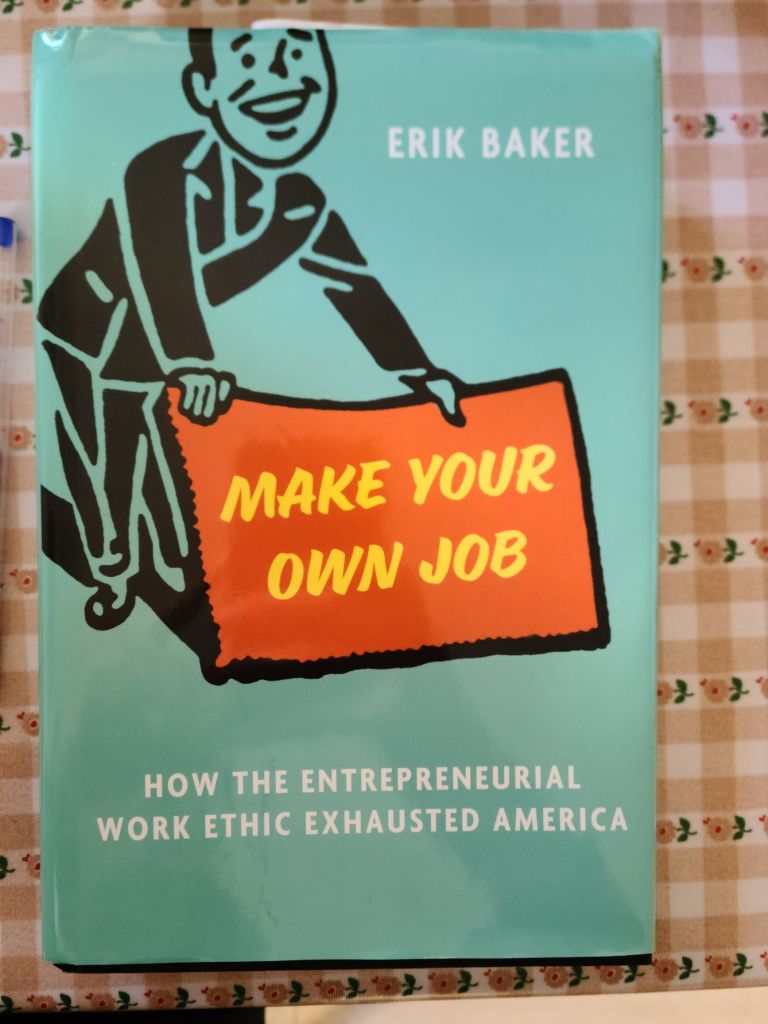

Erik Baker’s impressive Make Your Own Job (2025) might not completely dispute the broad outlines of Lordon’s periodization; however, Baker’s research suggests that the actual historical record is not quite so neat (as historians are wont to do). Most notably, Baker challenges one of the prevailing assumptions that many thinkers on the left hold about work: that characteristics such as flexibility, adaptability, and creativity, first arrived with the thoroughgoing transformations of the conditions and practices of labour in the 1970s. Situated within the intellectual traditions and economic movements of the United States, Baker presents a revisionist history of the idea of work, less as a linear sequence of regimes and more as an alternating back and forth between different ethics, plural, which emerge, become dominant, and then recede into residual status as material conditions change – always retaining the possibility of being reactivated and mobilized afresh under different historical circumstances.

A work ethic, Baker explains, is first and foremost a moral code, a set of values which both informs an individual’s understanding of their private labour and how it relates to the social totality. It follows that the primary ideological task of any work ethic is to reconcile subjects to their status, situation, and condition as workers. Baker highlights that this was a particular pressing task in the United States which, by the late nineteenth century, had to come to terms with the permanent existence of a class of proletarianized wage workers in a so-called classless society. For a republic which coupled the economic ideal of individual self-proprietorship with political liberty, this mass of dependent proletarians threatened to undermine the civic foundations of the nation-state. Rooted in the imaginary of an agrarian democracy, to become American one had to become self-sufficient, to occupy and tend a plot of land. The virtues of citizenship were cultivated through independent husbandry: of the self, the family, and the homestead – virtues which could not take hold in the factories, railroads, and industrial shipyards, where workers were broken down into parts, into ‘body-men’.

With the closure of the frontier and the dissolution of its agrarian inflected moral code, a new ethic needed to be formulated, one which could take shape and supply meaning to the dehumanizing conditions encountered by the legions of industrial workers. This ideological crisis is resolved through the ‘industrious work ethic’, which ‘emphasizes duty and the virtue of persevering without questioning assigned tasks or expecting much reward’. What is important for this work ethic is not the particular quality or skill that is being executed or performed but rather ‘the simple fact that a person is working hard’, that they are a productive member of society, as opposed to feckless shirkers and reprobate parasites. Through nostrums of persistence and sobriety, workers are encouraged to take pride in their role as the producers of modernity, regardless of the grim nature and unpleasant settings of their labour.

One of the arguments put forward by Make Your Own Job is that the industrious work ethic is singularly incapable of mediating one of capitalism’s most pernicious contradictions: the dialectic whereby capital reproduces itself through the expulsion of labour from the active workforce. This can take the form of technologically induced layoffs, which makes the obsequiousness inculcated by the industrious ethic as obsolete as the particular lines of work that are being phased out, mechanised, automated, or simply eradicated. In this regard, whilst the industrious work ethic can be said to pacify employees during periods of economic boom and steady expansion, it is incapacitated in times of crisis and retrenchment, in moments where there is an acute scarcity of jobs to absorb the surplus multitudes who nonetheless have to live off the sweat of their brow to survive. What happens to the work ethic during these periodic downturns where there are not enough stable jobs to go around?

Out of the crises that beset American industrial capitalism at the turn of the twentieth century emerges the ‘entrepreneurial work ethic’. Whereas the industrious work ethic preached diligence, habit, and character, the entrepreneurial work ethic thrives off charisma and the force of personality, of searching out and creating opportunities for oneself. Rather than passively wait for assignments, entrepreneurial individuals actively draw on their ingenuity and inventiveness, identifying niches in the market through which they can create new products and services, conjuring the future out of thin air. In doing so, the entrepreneurial work ethic combines both value creation, often moving into and taking advantage of nascent industries, technologies, and desires, and harnesses the psychological benefits of exercising control over one’s labour. Confronted with the absence of secure work, the entrepreneurial work ethic promotes the material and spiritual uplift of taking back control of your working life, putting your passions, interests, and talents to work. Hence the mantra of making your own job.

Engaging with two truly cursed genres of writing, popular psychology and management theory textbooks, Baker traces a history in which the entrepreneurial work ethic is nestled within and modulates the material and intellectual transformations that have structured the US economy since the late nineteenth century. Itinerant salesmen jostle alongside the cosmic manifestations of Henry Ford, multi-level marketing schemes are sequenced with new age philosophy. Even the Koch brothers make an appearance, peddling the self-reliant, autonomous, and independently minded entrepreneur as an antidote to the collective solidarity fostered by trade unionism. Put with excessive simplicity, the industrious work ethic is dedicated to the production of the same, with its representatives frequently depicted as maintaining the smooth functioning of vast corporate machines, whilst the entrepreneurial work ethic engages in the production of difference, in creative problem solving. Entrepreneurs do not so much reproduce the present but rather intuit the future, whose arrival they set out to actualize.

For Baker, the entrepreneur is most powerfully symbolized by two interconnected social types: the Silicon Valley tech bro and the networked gig worker. Grit and grift, perseverance and passion, moxy and opportunism coalesce in these ‘myth attractors’, who make their job an extension of their selves. This symbolic amalgamation and condensation equally underscores the ideological operations at play in the entrepreneurial work ethic. In appealing to both the asset rich and those without assets, the entrepreneur promises to overcome the trauma of class society. Everyone can market their joys; anyone can put their dreams to work. The hierarchical divisions of production which fragment and fracture bodies and minds into repetitive gestures and empty routines are negated by the entrepreneur, who brings the mental labour of conception back in house, so to speak. Not only does the entrepreneurial ideal heal the alienated, divided self of industrial capitalism, but it also dissolves class antagonism. Capital, in the guise of the entrepreneur, refashions itself as a virtuoso worker, a creator of things, not least of which is jobs. Workers meanwhile are transformed into human capital, bundles of breathing and bleeding assets that seek returns on their investments, such as university education.

Part of the enduring appeal and resonance of the entrepreneurial work ethic is its hostile relationship to existing forms of work. Baker attributes its tenacious hold on the American psyche to precisely ‘its ability to metabolize discontent with the present order of work’. With its proclivity for creativity, novelty, and invention, the entrepreneurial ethic passes itself off an anti-work ethic, one which sets out to destroy the rigidity, monotony, and banality of employment. As Baker neatly summarizes, ‘to make your own job is to refuse the job another might impose on you’. Individuals retain the ‘power to create better work for themselves’ and with more meaningful forms of labour, a better quality of life. Confronted with the proletarianization of body and soul, the anti-work ethic of the entrepreneur affords an opportunity to individuate oneself through a labour of one’s own.

The refusal of work is one of the frames through which I’ve proposed reading the fictions and films of outlaw appropriation. From the stick-up artists to the safe cracker, outlaws similarly resist the imposition of industrious forms of work, work in which your thoughts, feelings, and actions are not your own – and pay like shit. Like the entrepreneur, outlaws make their own jobs, using their intellect and inventiveness to pull cash out of thin air – or from down the barrel of a gun. Yet with their reliance on imaginary labour and the circulation of signs, figures like the counterfeiter, the forger, and the grifter appear like offshoots of the entrepreneurial work ethic itself. Such proximity between the profit-making capacity of the imagination and fraudulent schemes does not go unmentioned in Make Your Own Job, which includes the escapades of Napoleon Hill, a con man turned self-help guru, a line which consistently threatens to blur.

Make Your Own Job clearly delimits and demarcates its geographical and historical area of study. Through a sequence of ideologues, spiritual revivals, and cultural works, Baker presents the cyclical reappearance of entrepreneurship as it encounters, destroys, and creates jobs in its own image. Yet the processes and formations that Baker detects within the United States might also be said to expand and extend across the horizon of global capitalism. In this regard, wherever there is a limited supply of fulfilling work, wherever jobs are soul-crushingly boring and dreams for better days cannot be expressed collectively, the entrepreneurial work ethic makes itself available as a tonic to material and personal stagnation.

One recent example of this ideological worlding is Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s grind thriller Cloud (2024) which, in Baker’s terms, registers and reflects on the difference between industrious and entrepreneurial work ethics, and the forms of life each makes possible. Set in contemporary Japan, the film establishes the tension between the routines of industrial labour and the fluctuations of information-based work through Yoshii, a diligent but disinterested factory worker who tests his mettle through his side-hustle as an online reseller. Cloud opens with a scene of appropriation and opportunism, as Yoshii clears out the stock of a failed health business at a ruthlessly low price and then resells the products online at a significant mark-up. To succeed as a re-seller, Yoshii needs to have an exceptional sense of what products will sell in the near future for a higher price than he paid for them, a kind of clairvoyance and betting on the movements of consumer desire.

This openness to chance and unpredictable possibilities contrasts sharply with the deadening monotony of Yoshii’s work in an industrial launderette, where he is simply expected to perform the same task over and over again. The success of his opening venture enables him to break with industriousness and to turn down the offer of a promotion. Rather than crossover into the staid hierarchies of the managerial class, Yoshii backs his intellect and cognitive faculties and decides to make re-selling his full-time occupation. The repetitive and banal characteristics of machinic labour are replaced with the dopamine rushes and emotional intensities of re-selling and giving ones self up to the chronic instability of the market. Yoshii, in other words, creates his own job. However, if he creates his own job, his actions also create an array of enemies: there’s the spurned former boss, the inventor he screwed over, the friend whose ideas he stole, the desperate hired hand recruited the social media forums to hunt Yoshi down. Wanting Yoshii’s blood, this misfit band conspire and their plot pushes Cloud away from work and into a revenge film, with a showdown in an abandoned factory, where revenants with no future pick over the remains of the industrial economy, as the living slowly descend into hell detached from collective history altogether.