In The Double Shift (2024), Jason Read explores the stranglehold work has over life – the bodily, practical experiences of everyday existence – and consciousness – the mental forms of representation used to make sense of those experiences. For many of us, work is not only the sole (legitimate) means of sustaining our material needs (and indulging our fancies whenever possible), it is also where we find recognition and fantasize about better days to come. Work thus organizes our desire for things and invests our individual acts of labour with a heightened sense of purpose or mission.

Perhaps even more surprising is the extent to which in recent years work, as a practice and ideal, has begun moonlighting in areas of life seemingly removed from productive economic activities. Read draws attention to a number of commonplace idioms that are in fact saturated by the imaginary of work: we work on our physiques, our personal relations, our selves.

For classical Marxism, work belongs squarely to the economy, the domain of production, the brute arena where human muscles and brains are expended and commodities circulate without meaning or greater symbolism. Ideology, on the other hand, belongs to the sphere of reproduction, the realm of attitudes, beliefs, and values, the ideals which make people tick and convince them to return to their sites of exploitation. One of the significant contributions of The Double Shift is its upending of this traditional base/superstructure model, which Read replaces with an ‘ideology of work’, one which ‘connects experiences, life with consciousness, with the ruling ideas and ruling consciousness’. Ideology is not external or above the economy but rather the relation between material conditions and their representation.

Fundamental to the account offered in The Double Shift is the labour relation. In exchange for the money needed to secure essentials, we must handover our capacity to work to an employer. Everybody has to make a living somehow. Such common sense, Read notes, both naturalizes an economic relation as a fact of life and obscures the contributions of others within the labour process. The attachment to work, as source of sustenance and site of salvation, as well as anxiety and fear, lies precisely in the ways it simultaneously structures desire, affects, and feelings through the wage and also acts on our ideas and images of personal transformation: work is ‘the answer to every problem, the solution to everything’. Work generates its own ‘spontaneous ideology’ that both encompasses all other ideologies and presents itself as originating from anthropological necessity. In other words, the wage relation produces and reproduces a structure of feeling and imagining, a way of looking at and thinking about the world.

In addition to operating at a pre-ideological affective level and a trans-ideological mythic level, the politics of work makes its presence felt in both the concrete and abstract dimensions of labour. Concrete labour refers to a particular activity or task. Satisfaction can be derived from the application of a set of skills and intelligences, in the ethics of a job well done. Miseries, meanwhile, follow in the wake of being reduced to fragmented, repetitive, and mindless tasks, to a life defined by a single occupation. Abstract labour, in contrast, relates to the generic capacity to have capacities, to remain ‘productive whilst retaining potential’. A sense of pride and duty can be found in simply having a job, in being a productive member of society. As standard and norm; however, abstract labour disciplines and imposes conditions on concrete activities. Individuals are compelled to maintain certain levels of productivity, to conform and modify their behaviours, practices, and pace of work. The dual character of labour, then, functions as the linchpin for the ideology of work.

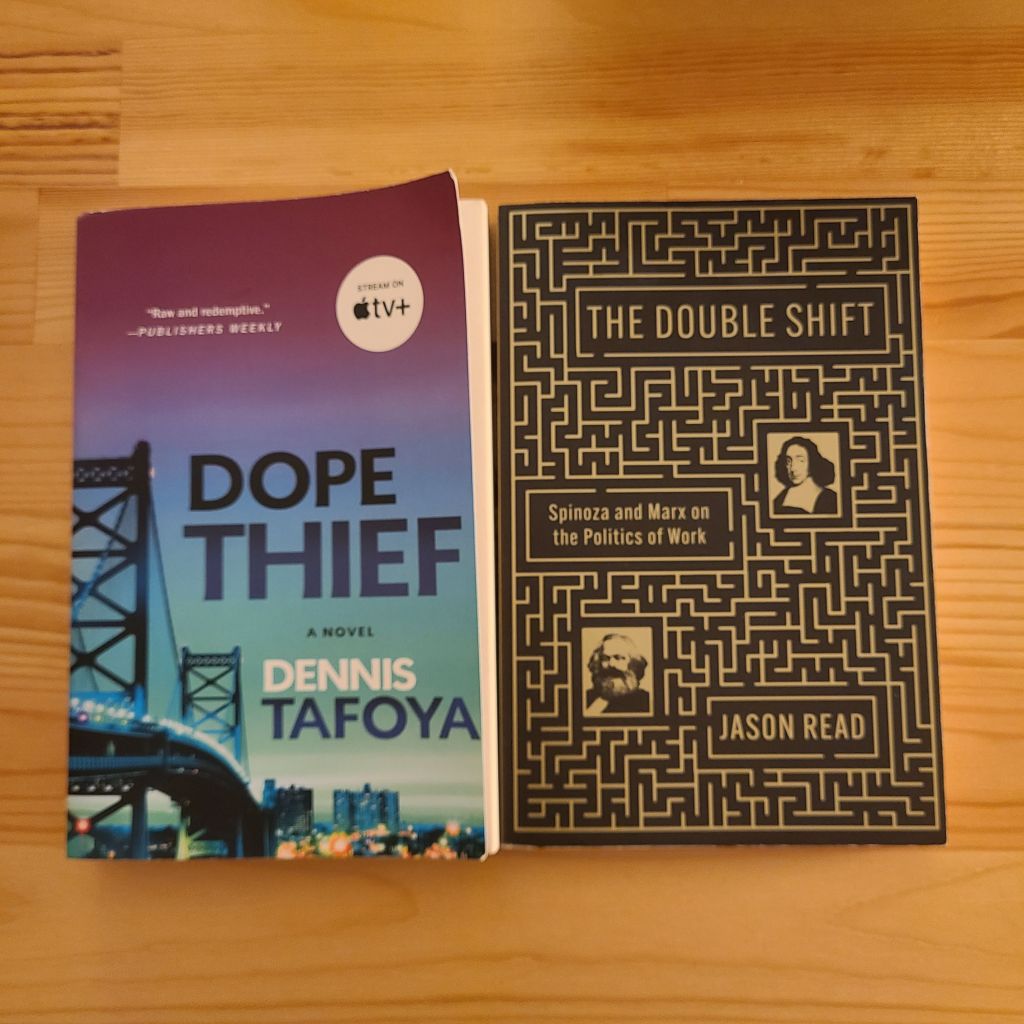

A work of philosophy and cultural theory that maps out the contemporary politics of work, The Double Shift might be a surprising resource for ideas about outlaw appropriation. To paraphrase the junkie stick-up artists in Dennis Tafoya’s Dope Thief (2009), one of the main dilemmas for outlaws is to explain the presence of money but the absence of work. For Ricardo Piglia, the dominant affect such outlaws feels towards waged labour is resentment. Money earned through work is humiliating: as an employee, your actions, speech, and gestures are scripted by an other – a boss, a manager, an overseer. Alongside this dispossession of authorship – or scripting power [for another time] – there is crude material dispossession too: no one has ever amassed life altering wealth working forty hours a week. In Read’s terms, outlaws could be said to deviate from both the ‘affective composition of labour’ – the wage is no longer perceived to make an attractive life possible – and also disavow the ‘mythic composition of labour’ – the fairy tales that with enough dogged hard graft you can transform your life.

At first blush, the fictions of outlaw appropriation might even be said to respond to Read’s broader rallying cry about the need to denaturalize work. As staged in texts like Dope Thief, outlaws actively decouple the satisfaction of material needs from the demands of waged work, temporarily enacting a rupture with the prevailing reproduction of social relations – they are outlaws after all. To twist Mario Tronti’s formulation, outlaws refuse to sell their labour-power as a commodity and, by fleeing the office, the assembly line, the distribution centre, they set about writing their own scripts and counter-myths. Such utopian traces have long drawn the interest of thinkers like Fredric Jameson, who find in these criminal enterprises moments of unalienated labour and pre-figurations of a collectivity to-come. In terms of the ideology of work, outlaws reject the social command to subordinate their desires to the needs of abstract labour, to its nostrums of civic duty, restraint, and forbearance.

At the same time, the anti-heroes of outlaw appropriation rarely sit idle. More often than not, outlaw appropriation relies on the execution of some preternatural talent, personal quality, or craft which is inseparable from the act – and maybe the art – of appropriation. This dialectic does not escape Read, who includes ‘black market melodramas’ (Michael Szalay’s apt term) like Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul in a discussion of the role of work in making and unmaking the self. On the surface, Walter White’s transformation from a mediocre high school chemistry teacher into the feared drug kingpin Heisenberg is an archetypal outlaw story, of exiting the straight world of middle-class suburban America. However, it is only through the activation of his intellect that White discovers his virtuosity as a crystal meth cook, one whose signature blue hue authenticates his product and acquires folkloric status across New Mexico. Rather than a break from the drudgery of waged work, it is precisely White’s skill, knowledge, and dedication as a worker which enables him to guarantee his family’s future and acquire a type of cult status. As Read summarises, for White, ‘crime is work’. Indeed, across its five seasons, the show tracks the changing conditions and composition of White’s labour, as his lab moves from a beat-up RV to an industrially designed factory and finally to dark kitchens, a sequence inflected by the subsumption of capital. Read suggests that the narco-fantasy which formally organizes the narrative enables Breaking Bad to process and give expression to far more quotidian tensions, pressures, and anxieties, such as downward mobility and the search for respect. By virtue of his self-mastery through work, Walter White is more readily a figure of right-wing myths of independence, self-reliance, and hierarchy, than a left-wing myth of resistance, egalitarianism, and collective struggle. In the level of the cultural imaginary at least, outlaw appropriation functions as the ‘other scene’ of waged work, a site where fears and hopes around employment can be displaced, recombined, and dramatized, as much affirming as disqualifying the ideology of work.

In other words, by refusing to work for a wage, outlaw appropriation calls into question the otherwise spontaneously lived ideology of work, making it perceptible and therefore alterable. On the other hand, outlaw appropriation engages in a re-valorization of concrete labour and, by extension, fuels the mediated and mythic images of individuals re-asserting ownership over their lives through work – as embodied by figures like Walter White. A dialectic of refusal and re-mythologization could be said to run through and organize the fictions of outlaw appropriation. To try and bring these admittedly loose reflections on The Double Shift to a close, I would like to briefly return to the ‘mythic composition’ of labour and to the question of how the circulation of narratives conditions beliefs, inculcates habits, and structures action.

Unlike black market melodramas like Breaking Bad, the crew at the centre of Dope Thief are neither exceptionally gifted nor invested in the symbolic order of middle-class America. Rather they are junkies – or in the process of becoming junkies – for whom ‘it’s a straight line’ from ‘Money’ to ‘Dope’. That is, appropriation without accumulation. In this respect, Dope Thief registers the collapse of the American Dream from the perspective of ‘the below the below’ (McKenzie Wark), for whom it was only ever an illusion and who are now contending with the ruined infrastructure and decimated lives of millennial USA. Even the homegrown meth industry is threated by the ‘invisible hand’ of the market, one character remarks, as production is outsourced and off-shored.

Whilst Ray and Manny do not work, they nonetheless pull off jobs: acting on tip offs from rival drug dealers, they stick-up and rob trap houses, providing an invaluable service in the ecology of narco-capital. Ray and Manny complete these jobs with the help of stimulants – taking bumps of coke before each break-in – but also simulation: their robberies are staged and conducted as if they were DEA raids. As Ray explains to a new accomplice: ‘you’re not a Fed, you just play one on TV, get it’. By performing as, and impersonating federal agents, the crew is able to take control of potentially volatile situations and transform them into their own scenarios, ones in which they can capture attention and take advantage of pre-conditioned responses: ‘no one’s going to draw on a Fed unless he’s fucking insane’, Ray reasons. Disguised as DEA agents, Ray and Manny are able to extract a degree of security as they rip-off low-level operations.

There is a resonance here between the guerrilla stage setting, improvised directorial vision of Dope Thief’s motley cast of actors and the ‘mythic composition of labour’. Put simply, the labour relation is not only experienced spontaneously through feelings but also consciously reflected on and conceptualized. The mythic composition of labour, in other words, refers to the ‘narratives we use to make sense of it, and orient ourselves’. From within the context of the United States, Read surveys the alternations of this myth from the bootstrapping characters who populate the novels of Horatio Alger to the business gurus of Silicon Valley, for whom work is about finding your passion. Perhaps another illustration of the mythic can be sourced from within hustle culture and its grind mindset, to the belief that with enough moxie – and followers – you will be able to manifest your dream life. (A set of narratives which have their own outlaw myth attractors, like Anna Delvey, who prey on the fictitious nature of value today).

One of the tasks of ideology is to produces myths that can reorient desire and striving so that self-worth, for example, is inextricably bound up with having a job, or that aspirations for a better quality of life are exclusively channeled through work. Interpretation plays a key part in this social process. The way we read signs is shaped by the history of our previous encounters and these accumulated experiences in turn shape our future interpretations and responses. In this sense, the circulation of narratives, images, and stories through the imaginary are not simply passively consumed but also actively acted on. For Read ‘the imagination is a “meta-conduct of conducts” in that it determines not actions but how one thinks about the very possibility of action’. In a surprising plot twist, the immaterial ‘is itself the condition and ground of the material actions of bodies’ – the imagination makes action possible.

Drawing on the work of French media theorist Yves Citton, Read suggests that through the consumption of mass culture, we begin to form certain habits, adopt particular modes of conduct, and learn gestural relations. ‘Our immersion in the world of a novel, film, or video game’, Read glosses, ‘is not something cut off entirely from our living engagement with the world, but a modification of it’. That is to say, we learn how to act and perhaps react to situations and events in the ‘real world’ through our attachments to cultural texts, works which prepare and train our perceptual, motor, and cognitive responses to stimuli. Viewed in terms of interpretation, cultural forms affect how we read and negotiate situations, ranging from the viral resurgence of conspiracy theories at the level of the political, to taking social cues and hints at the level of the personal or intimate.

On another level, this can take the form of imitating certain traits, mannerisms, or affectations – forms of metalepsis where the world of the imagined action crosses into the world of physical bodies. As well as being a novel about working through trauma, Dope Thief is intensely interested in the mediation of experience, in how the scripts and scenarios which gush ubiquitously through popular culture can be adapted, re-interpreted, and re-purposed. Ray in particular is presented as a reader and interpretor, a consumer of pulp fantasies who thinks of himself ‘as a professional. Or as acting like a professional’. During debrief after a successful raid, Ray remarks that ‘they call it the command voice […] Your problem is you don’t watch enough TV. One or two episodes of Cops’ll tell you anything you want to know about managing the criminal element’. By imitating the mannerisms, styles, and intonations of the police, as represented in the culture industry, Ray is able to masquerade under the hard power of the state, but which is only backed up by ‘soft power’, with how the imagination affects bodies. Ray mimics the comportment of state agents but, in doing, invents a new role and occupation for himself as a dope thief.

Theorized as conductors of conduct, individual works of culture rely on ‘meta-scenes’: ‘the general matrix of possible and desirable actions drawn from a general economy of affects and attention’. These sorts of conventions and inherited expectations are especially visible in genre pieces. Dealing with a bout of insomnia, Ray watches a film about an outlaw couple on the run and notes that ‘of course they were doomed, that was the movies, but he couldn’t think of a lot of bank robber stories that ended up with they live happily ever after’. Yet this pervasive sense of no future – Ray cannot think of ‘any kind of stories’ which end happily – bleeds into the way he interprets his own line of work: ‘they were as doomed as the goofy bastards they were ripping off’. The ways in which myths are organized in the imagination both shapes the action of Dope Thief but it is also a sensibility the novel actively attempts to re-circuit and re-link through its own take on resurrection and second lives.

At their strongest, fictions of outlaw appropriation break with what Read sees as one of the most ‘entrenched and pervasive’ meta-scenes in in the culture industry: ‘that of the isolated and exceptional individual’. Dramatized around the lone hero, ‘individual action, rather than collective action, is the meta-scene of our imaginary’. This meta-scene both structures the way structural processes are personalized, as individual failures or weaknesses, but can also become crime scenes as individuals re-enact action sequences – like the Aurora theatre shooting. Outlaws, such as those in Dope Thief provide a sort of challenge to this meta-scene of individual action, emphasizing and affirming the role of collaboration and communication in pulling a heist off. That said, the majority of outlaw scenarios remain attached to what Jed Esty has called the ‘weak state mythology’: a set of myths in which individuals have to step in and assume responsibility for rescuing themselves and defending their communities in the palpable absence of more properly collective institutions. Moreover, as Justin Kruzel’s 2024 film The Order makes clear, neither does the left have a monopoly on ‘bookish’ outlaws, who script their actions from fiction and invent counter-mythologies to liberal capitalism.

The mythic composition of labour sets out to attract flows of belief and desire, to invest work with a totemic significance, to consecrate even the shittiest job as simply the origin story of self-transformation. These narratives, stories, and images course through the culture industry, capturing attention and passing through bodies, modifying what actions are imagined as possible – and desirable. But, as Dope Thief explores, these scripts can be put to work too. Ray and Manny are two guys who wear ‘cop jackets and badges’ sourced from flea markets, yet these props enable them to move with the illusion of force to ‘take control of the situation’. Taking inspiration from television cop dramas, Ray and Manny are able to harness fears felt towards the state – in choice language, ‘only a stone retard was going to throw down on a Fed’ – and meta-script the actions of the dealers they are ripping off, appropriating the dope through coercion certainly but also through performance, a type of soft power. At risk of exaggeration, they are almost junky auteurs until, predictably, things go south, and contingency reasserts itself within even the most tightly rehearsed plan. This question of soft power, the imagination, and their relation to outlaw appropriation will be the subject of my next post (well hopefully), which picks up on these threads through Yves Citton’s recently translated Mythocracy.