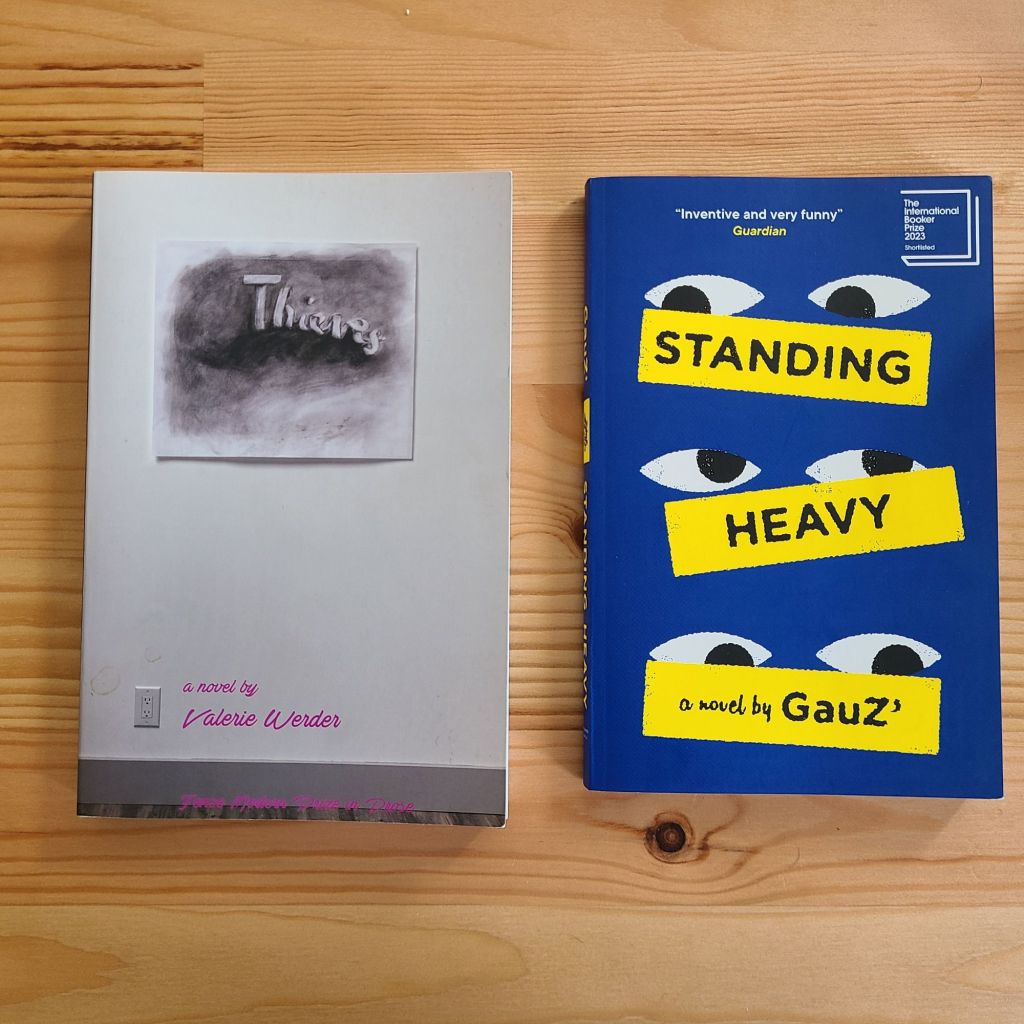

By chance I recently finished two novels in which the commodity, that elementary form of the capitalist mode of production, acquires a voice and personality. They approach this personification of things, however, from diametrically opposed perspectives and interests. Commodities in Valerie Werder’s auto fictional novel Thieves (2023) are the object of the appetites of the body and the desires of the mind, desires that are not so much motivated by the compulsion to consume but by the search for a life outside the order of value. The heroes of Thieves, in other words, are shoplifters. In sharp contrast, the commodities that congregate in GauZ’s Standing Heavy (2022) are subject to the vigilant attention of security guards, the workers hired to protect the commodity’s value form and who record to its secrets, its yearnings and aspirations.

Shoplifting for the characters of Thieves is identified as one possible solution to the demise of alternative forms of living in twenty-first century USA. An eccentric bildungsroman, Thieves follows Valerie from her unexceptional suburban youth to New York city, where she finds employment writing copy for an art gallery. A teenage shoplifter, Valerie’s dormant talents are reactivated by Ted, a charismatic thief and furious lover, who draws her into his nomadic life, one which disavows the ethical imperative to work. Valerie and Ted’s relationship is supplemented by Ted’s ex-girlfriend, Virginia, who helps periodize the novel’s present. Completing a dissertation on the verité filmmakers from the seventies, Virgina notes that the conditions which allowed these auteurs to refuse to distinguish ‘art from labor from life’ no longer hold true. The dream of the ‘no-job bohemian’ who is free to experiment with modes of existence that overcome the division of labor has been negated, Virgina suggests, by ‘rising rent, for one’.

Conceptually invested in the mission, language, and possibilities of the historical avant-garde, Valerie, Ted, and Virginia find themselves stranded in an era in which such forms have been eliminated by capital. Flight remains possible but it now takes the shape of a subtraction or withdrawal from the totality of social relations: ‘not buying was the easiest way to not exist. It could be incidental, a condition of poverty, or strategic or both. Buy something; you leave a trace. Leave a trace; you exist. Stealing was equivalent to not existing’. Shoplifting for the friends becomes a kind of practice, one which allows them to refuse their subjection as consumer, citizen, or worker. The image of shoplifting is given a slight reconfiguration here. Detached from associations with impulsive acquisition and conspicuous consumption, stealing is instead directed underground, towards states of invisibility and erasure. Slipping through the cracks of the spectacle – both as commodity and surveillance – the thieves stage a kind of disappearance: going off-grid within the metropolis itself, vanishing into the structures of modernity.

Standing Heavy is similarly interested in the experiences, passions, and motivations of characters who live a semi-clandestine existence. However, rather than white hipsters looking for a way out of normative social conventions, Standing Heavy is rooted among undocumented migrants who have left the Côte d’Ivoire for the capital of the Francophone world, Paris. The stories, desires, and pressures that circulate through Standing Heavy, then, are shaped by and explore the colonial character of modernity and the dynamic relation between periphery and metropolitan core. Almost existentially averse to any action that might aggravate an encounter with the state, Standing Heavy arguably dramatizes the reverse journey to that of Thieves. Characters aspire to pass from precarious non-existence – stalked by the prospects of deportation – to securing legal recognition as credentialed citizens. Ironically, the Ivorian migrant community establishes its niche in the lower rungs of the security industry, first as guards before taking over the sector and controlling it through their own companies and informal networks.

The novel registers this flow of migrant labor across three distinct periods: ‘Bronze Age: 1960-1980’; ‘Golden Age: 1990-2000’; and ‘The Age of Lead: 2011’. Focalized around a different character – who nonetheless relays knowledge, contacts, and opportunities to their narrative successor – these historical moments allow Standing Heavy to encode the changing composition of security work as it relates to transformations within the economic landscape of France. Over the course of this slim novel, the factories of high industrialization are disassembled, broken down into ‘skeletal remains’ and investment is funneled instead into the shopping malls of contemporary consumer desire. There is a shift from protecting the sites of fixed capital – in bother their active and hibernating states – towards the profusion of circulating capital. At the same time, this half-century arc also encompasses the faltering trajectory of the revolutionary project within the Côte d’Ivoire: the utopian energies of the Bandung era give way to intellectual despair in a present constituted by sprawling shantytowns, characterized by precarious work and menaced by predatory violence.

These periodizing sections are interrupted by the insurgent present of any anonymous security guard as they complete a sort of ‘tour of duty’ around various high street outlets along the Champs Elysees. Whereas the ‘ages’ reflect on the diachronic transformation of relations between subjects and social structures, the interruptive presents engage in a more synchronic registration. A retrospective mode gives way to an effervescent impressionistic style, one in which thoughts, sensations and scents are distilled in vignettes or tableaux. Time becomes space: namely, the space of retail, which has its own infernal temporality, syncopated by repetitive loops of inoffensive pop songs. Organized around headings such as ‘Version Anglaise’ or ‘First Genetic Theory of the Antilles’, the entries range across sociologically inflected observations, speculative theories, mantras, codes, vernaculars, and tactics. Combined, they form a sort of psychic archive or set of index cards, a mode of workers’ inquiry. What is captured are the stimuli, fashions, and manias of consumer desire, as well as the embodied labor that enables such encounters to take place – at least at the point of sale. Given that we are in Paris, perhaps it wouldn’t be completely inaccurate to say that Walter Benjamin’s beloved flaneur is given a uniform in Standing Heavy and pressed into the service of the commodity. Yet, as one of the characters is keen to highlight, the infrastructures of surveillance run on affect, as well as race: the Ivorian guards provide a racialized ‘feeling of security’.

In Thieves commodities confide in Valerie, sharing with her their intimate feelings. Whilst the stories of their circulation certainly trace the passage of socialized labor from the cargo container to the retail shelf, the tenor of this testimony is resolutely more personal, accenting hurt, abuse, and neglect. The commodities tell Valerie of how they have been ‘carelessly tossed’, ‘roughly handled’, ‘unpacked by bored store clerks’, and of their ‘ultimate refrigerated demise, slowly, consumed sparingly, responsibly’. An economy of inattentiveness perhaps. In contrast, the shoplifter is perceived as a savior, as a figure who breaks this cycle of abuse: ‘you saved us; you’ll love us’. To switch back into the language of Marxism, the shoplifter seems to liberate the commodity’s use value from its exchange value: direct appropriation emancipates the soul of the commodity, which now only exists for itself. As Valerie paraphrases: ‘they could no longer magically store all the world’s greed. They were themselves and only themselves’. Once commodities have been released from the world of measure, which is associated with equivalence and an ethics of abstinence, the sensuous plenitude of the concrete is recuperated, and now stimulates voracious appetites and pleases the bodies cravings, feeding its wants: ‘you could be ravenous, you bit’. The subjunctive is consummated. From the point of view of the commodity, shoplifting both frees the object from the circuitry of value and frees the subject from the censures, prohibitions, and restrictions of bourgeois sensibilities.

There is a lot more to say about Thieves than simply its ethos of shoplifting. The novel skewers the priorities of the art world and the related cynicism of much academic writing, whilst also striving to recover the body, voice, and labor of ‘unnamed workers’. Valerie both transforms art into high value investment assets through her writing but also de-commodifies the quotidian stuff of everyday life through her low-level thefts. Perhaps most intriguing is the examination of the role language plays in the production and circulation of value. Language is ‘a substance […] a lovely raw material’, an object which Valerie sculpts into forms that will increase the value of her clients’ portfolios. In this regard, Thieves takes seriously Paolo Virno’s claim that language itself has become the dominant means of production, that communication is central to the extraction of surplus value. It is through her linguistic virtuosity that Valerie is able to ‘draw cash from thin air’, to ‘conjure dollars from discarded words’. Alert to the ways in which stories can make money for their owners – which rarely coincide with their creators – Thieves resonates with and poses revisions to some of the work I’ve been doing off and on (mainly off recently) around outlaw appropriation – and which I would like to return to at some point this summer.